George Orwell’s first novel, Burmese Days, was first published in the United States on 25 October 1934, exactly ninety years ago today. The book - a scathing portrayal of British rule in Burma, based on Orwell’s own experiences - was initially turned down by several British publishers, who feared that it might be libellous.

Emma Larkin’s introduction to the Penguin Modern Classics edition of Burmese Days is available to read on our website by kind permission of the author and Penguin Random House. We are delighted to share the essay here today.

Emma Larkin: Introduction to Burmese Days

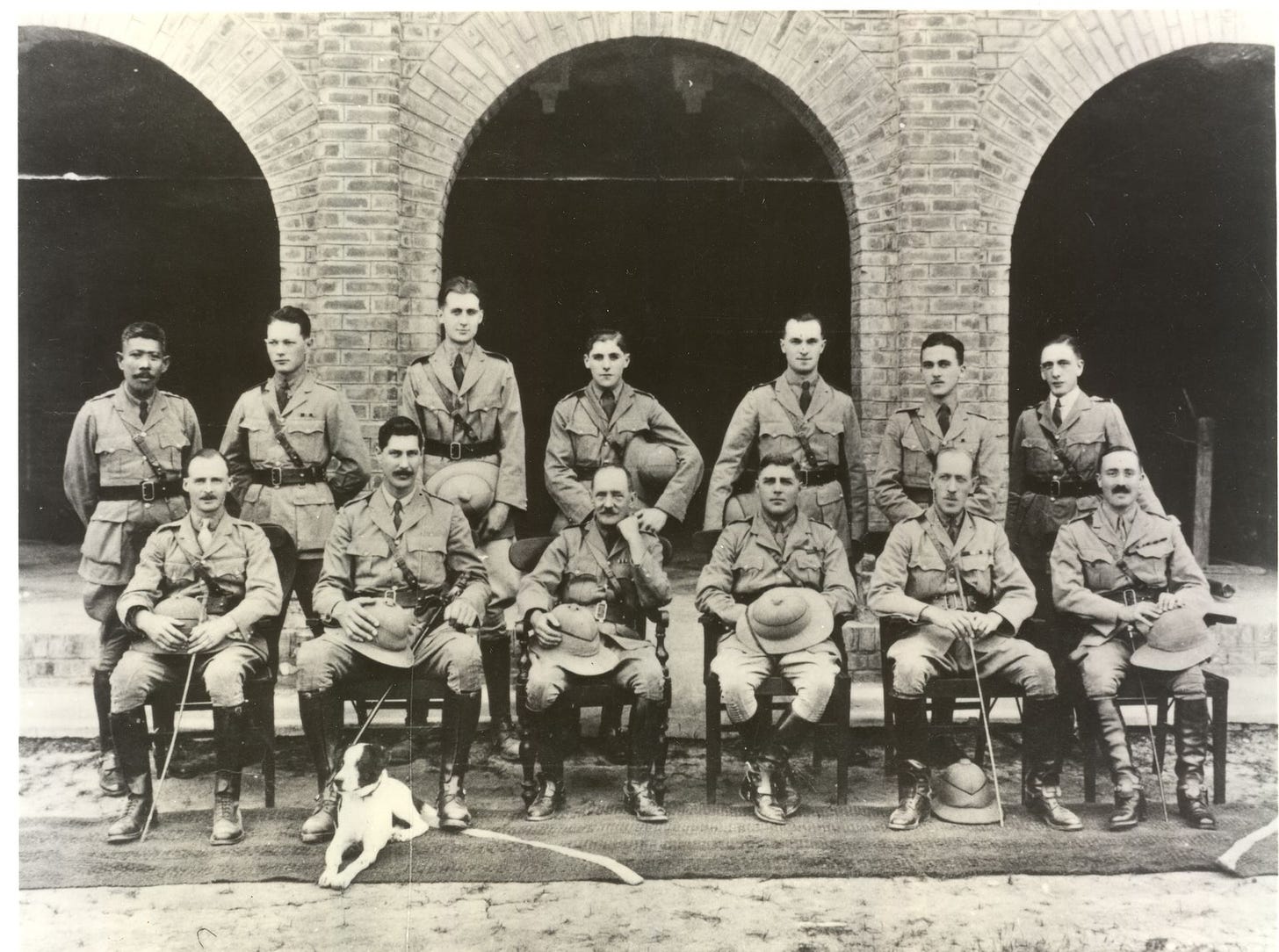

I have always thought that Orwell’s time in Burma marks a key turning point in his life. It was during those years that he was transformed from a snobbish public-school boy to a writer of social conscience who sought out the underdogs of society. As a policeman in Burma, Orwell saw the underbelly of the empire; not the triumphant bugles or bejewelled maharajas, but the drunken sahibs pickled by heat and alcohol in mildewed clubs, the scarred and screaming Burmese in their prison cells. He witnessed first-hand the devastating effects of repressive governance and it troubled him deeply. Unable to share his views with the enthusiastic empire-builders around him, he retreated like John Flory, the main protagonist of Burmese Days, “to live silent, alone, consoling oneself in secret, sterile worlds”.

In Burma, Orwell acquired a reputation as someone who didn’t fit in. Unlike his contemporaries, who prided themselves in being pukka sahibs, Orwell preferred to spend most of his time alone, reading or pursuing non-pukka activities such as attending the churches of the ethnic Karen group or befriending an English opium addict who was a disgraced captain of the British Indian army. Reading Burmese Days, it is easy to see how Orwell’s hatred towards colonialism must have festered in the solitude and heat, growing like a hothouse flower. Orwell later wrote that he felt guilty for his role in the great despotic machine of empire and became haunted by the “faces of prisoners in the dock, of men waiting in the condemned cells, of subordinates I bullied and aged peasants I had snubbed, of servants and coolies I had hit with my stick in moments of rage”.

Tormented by these Burmese ghosts when he returned to England, Orwell began to look more closely at his own country and saw that England also had its oppressed masses in the working class. The working class, wrote Orwell, became the symbolic victims of the injustice he had seen in Burma. He wrote that he was compelled into the world of London’s homeless and the destitute of Paris (experiences that would, a few years later, be collated in his book Down and Out in Paris and London):

“I wanted to submerge myself, to get right down among the oppressed; to be one of them and on their side against the tyrants.”

Down and Out in Paris and London was Orwell’s first published book and it was not until some years after he had left Burma that Burmese Days was ready for publication. Orwell’s publisher was initially reluctant to publish Burmese Days as he was concerned that Katha had been described too realistically and that some of his characters might be based on real people, making the novel potentially libellous. As a result, Burmese Days was first published further afield in the United States in 1934. A carefully censored British edition came out a year later, but only after Orwell altered the characters’ names and tried to disguise the setting. The Indian doctor, Veraswami, for instance, had his name changed to Murkhaswami (thus losing his derogatory nickname, “Dr Very-slimy”) and the Lackersteens became the Latimers. The town is called Kyauktada in the book and all references to its location in Upper Burma were removed. (The modern-day edition has been restored, with a few later editorial changes, to its original form.)

To facilitate some of the geographical disguises, Orwell drew a sketch-map of Katha for his publisher. On the map are roughly-drawn boxes marking the location of Flory’s house, the church, the bazaar, the jail and the British club – the physical and spiritual centrepiece of Burmese Days. According to Orwell, the real seat of British power lay, not in the commissioner’s mansion or the police station, but in this sad, dusty little building.

The club building still stands today, though it has since been turned into a government-owned cooperative. Where the garden used to be a riot of English flowers – larkspur, hollyhock and petunia – there are now large warehouses holding stores of rice, oil and sugar. The low tin roof of the club still hangs over a wooden verandah at the entrance, but the main room has been divided by a wall and is filled with desks and mismatched chairs. In Flory’s time, the interior boasted a mangy billiard table, a library of mildewed novels, months old copies of Punch magazine and the dusty skull of a sambar deer on one wall. Members of Katha’s British community whiled away interminable evenings with tepid gin & tonics and inane club chatter about dogs, gramophones, tennis racquets, the infernal heat and, inevitably, the insolence of the Burmese (older club members recalled the good old days of the colony when you could send a servant to the jail with a note reading, “Please give the bearer fifteen lashes”).

Most colonial memoirs I have read paint a jolly picture of life in Burma; making affectionate references to the butlers from Madras who prepared ice-cold shandy on river flotillas, ribald drinking songs around the club piano, shooting expeditions, dances. Burmese Days, however, is something very different. It is a portrait of the dark side of the Raj, chronicling sordid and shameful episodes of empire life.

Few of the characters in Burmese Days have any redeemable features; both British and Burmese alike are tarnished by the colonial system in which they live. As far as fictional heroes go, John Flory is painfully inadequate. He is cowardly, self-pitying, and carelessly cruel. In nearly every chapter he does something to debase himself, something for the reader to cringe at. But he is, like most of Orwell’s leading men, uncomfortably and almost unbearably human.

In defence of his harsh portrayal of colonial society, Orwell wrote simply:

“I dare say it’s unfair in some ways and inaccurate in some details, but much of it is simply reporting what I have seen.”

Emma Larkin is an American writer who was born, raised and still lives in Asia. She is the author of Finding George Orwell in Burma, Everything is Broken: Life inside Burma and, most recently, the novel Comrade Aeon’s Field Guide to Bangkok.