12 Orwell Prize finalists on the political books which shaped them

Winners will be revealed this Wednesday, 25th June

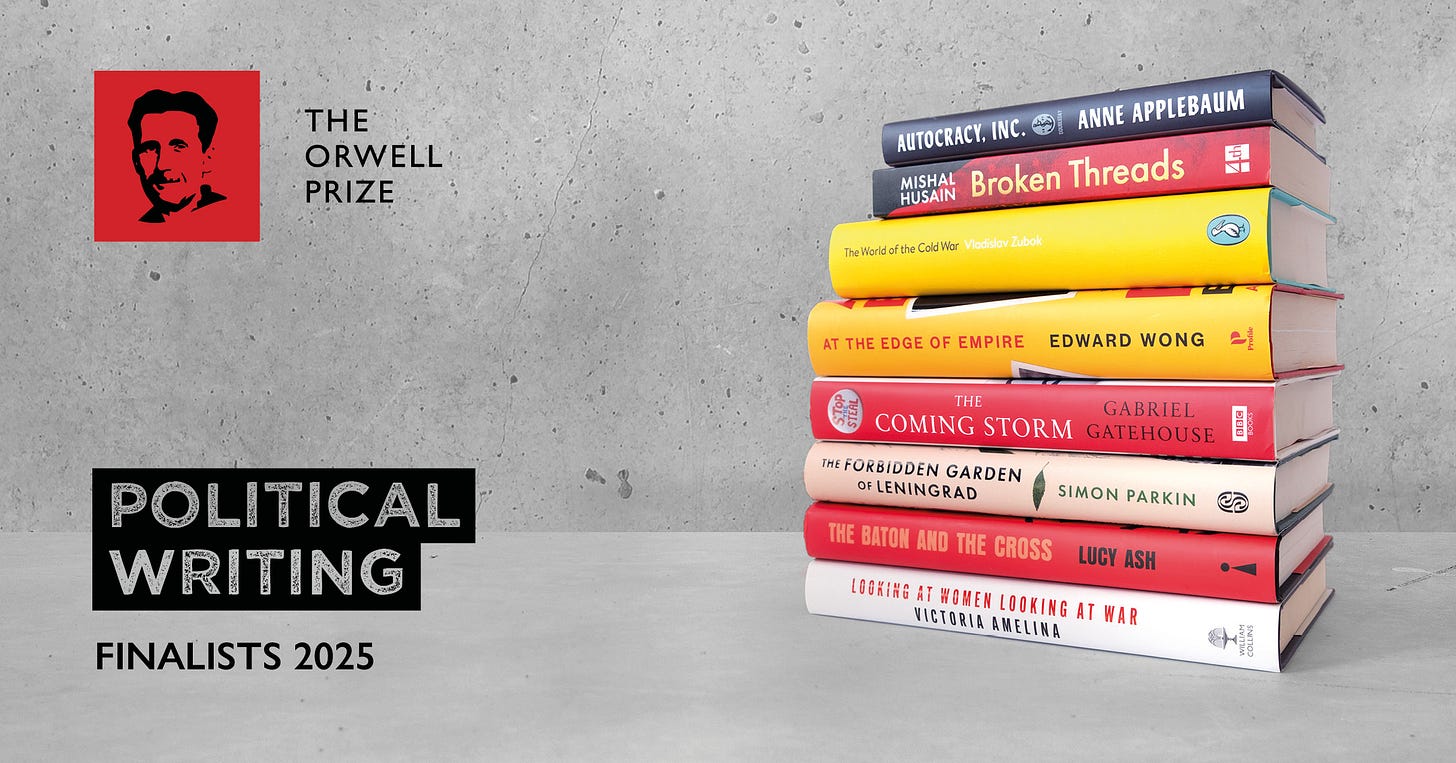

The Orwell Prize for Political Writing and the Orwell Prize for Political Fiction reward the books that best meet Orwell’s own ambition ‘to make political writing into an art.' The winners will be announced this Wednesday, 25th June, at the Prize Ceremony in London, and will each receive £3,000.

We asked the finalists to tell us about the political books which have had an impact on them - and why. Read on to find out what they had to say!

Live in London tonight: & Nathan Waddell on ‘Benefit of Clergy’

What do we do with great art made by deeply flawed—or even reprehensible—people? In tonight’s Orwell Festival closer, Helen Lewis (The Genius Myth) and Nathan Waddell (A Bright Cold Day) explore one of George Orwell’s most incendiary essays. There’s still a chance to grab your ticket here.

Friends go free, or use the code MURIEL at checkout for a 20% discount.

Political Fiction

Natasha Brown, Universality

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Perhaps that doesn’t sound like a ‘political’ book today. But of course the definition of that word isn’t absolute; it changes and adapts with our shifting social and cultural norms. I think that Austen masterfully used the conventional set pieces of country rambles, dinner parties and society balls as a backdrop to some really very substantive discussions about the politics of her time.

Noah Eaton, The Harrow

I spend far too much time reading 'political' books: biography, analysis, history, satire. It's hard to pick one, but Lyndon B. Johnson by Robert Dallek made me really think about the different ways in which people achieve their ambitions in politics

Donal Ryan, Heart be at Peace

Hans Fallada’s Alone in Berlin is never far from my mind since my sister bade me read it in my twenties, and Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem lingers too. A factory fitter and his wife can wage a tiny war against evil; a vacuum-cleaner salesman can become the architect of the Holocaust.

Elif Shafak, There are Rivers in the Sky

There are many political books that have affected me deeply, some of which I have read multiple times, each time discovering something new. The Possessed by Dostoevsky, The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir, Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, George Orwell’s 1984 and Homage to Catalonia, Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, Ivo Andric’s The Bridge on the Drina, Czeslaw Milosz’s The Captive Mind, James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time.... there are so many, and I believe Orlando by Virginia Woolf is also a very political book.

Jo McMillan, The Accidental Immigrants

Flying Free by Nigel Farage, and my reaction to it, powered the writing of The Accidental Immigrants. It’s Farage’s manifesto for the morality of the ‘pack’. It sets ‘us’ against ‘them’ and details how much (though actually how little) any of us has to care. It’s a license for inhumanity. And Farage – once a marginal figure in British politics – now has power. He’s connected to the US and the global far right, he has money, he’s getting religion, he’s in parliament and he’s dangerous. It’s important to know what the dangerous people say.

Political Writing

Lucy Ash, The Baton and the Cross

Teffi’s Memories From Moscow to the Black Sea. She was a St Petersburg celebrity and a satirist whose fans included everyone from Lenin to Tsar Nicholas II. She also wrote a brilliantly funny razor-sharp portrait of the Orthodox mystic Rasputin. She’s been compared to Chekhov, but she’s not nearly as well-known as she should be.

Edward Wong, At the Edge of Empire

There are many, but an important one for me is Slouching Towards Bethlehem by Joan Didion. It taught me that precise reporting combined with an intensely personal voice that embraces rather than avoids subjectivity can be the most effective way of representing, through words, enormous political and social change. The type of lens she applied to America, and California in particular, during the upheaval of the late 1960s is one that I came to realize could be used to look at many other milieus. I also read it at exactly the right time for it to have a great emotional impact on me: I was young and living in northern California and starting a career in journalism.

Mishal Husain, Broken Threads

Muslims Don’t Matter by Sayeeda Warsi. This book has not had enough attention since it was published last year, and perhaps that in itself illustrates why we need it. Warsi brings the receipts, documenting instances of violence and anti-Muslim hate that either barely made the news or were swiftly forgotten. This is an evidenced and important work, making the reader think about how differently communities can be perceived - and why.

Victoria Amelina, Looking at Women, Looking at War

(answered by friend, Sasha Dovzhyk)

Victoria was drawn to Ukrainian cultural figures who suffered for political reasons: from the Executed Renaissance of Ukrainian writers, purged in the 1930s, to the Sixtiers, repressed three decades later for researching the fate of the Executed Renaissance. The brightest Sixtiers were poet Vasyl Stus, killed in a Soviet prison camp six years before the collapse of the USSR, and artist Alla Horska, murdered in 1970, her monumental artworks destroyed in the Russia-occupied territories of Ukraine. ‘I have yet to become a part of this sad tradition of Ukrainian creatives finding out what happened to their dead colleagues’, Victoria wrote.

Simon Parkin, The Forbidden Garden of Leningrad

Laurent Binet’s HHHH attempts to tell the story of the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, a member of Hitler’s cabinet who was killed by two men, a Slovak and a Czech, who were recruited by the British secret service. The historical story is obviously compelling, but Binet opts to include and interrogate his own research process in the telling of the story, exposing his natural temptations to fabricate or fudge details, or to bend the historical story in subtle ways to make the work more novelistic or politically useful. It’s an honest and challenging account of the writer’s task to impose form and structure onto messy historical events, and one that I have found useful in my own work.

Gabriel Gatehouse, The Coming Storm

There are many ‘political’ books that have affected me. One that comes to mind is Life and Fate by Vasily Grossman. Sometimes described as the Soviet War and Peace, I first read it in 2011 while reporting from Libya on the rebel war against Colonel Gaddafi. Grossman weaves a complex tapestry out of the stories of individual lives that together make up a great political event. To immerse yourself in those stories, especially during a time of conflict, is to gain not only a deeper understanding of complex situations; it can breed a radical empathy with those who might otherwise remain faceless villains.

Anne Applebaum, Autocracy, Inc.

The Captive Mind, by Czeslaw Milosz, the Polish poet. He describes better than anyone else the psychology of collaboration, as well as what it feels like to live in a repressive state.

Subscribed to site with enthusiasm - being a major fan of Orwell.

However I am unsubscribing with haste as I read Jo McMillan's tribal assessment of Farage as 'dangerous'. I require a bit more thoughtfulness than that. I feel sorry on Orwell's behalf if this is the standard of your contributors.