12 Orwell Prize finalists: their books in their own words

Winners will be revealed 25th June

The Orwell Prize for Political Writing and the Orwell Prize for Political Fiction reward the books that best meet Orwell’s own ambition ‘to make political writing into an art.' The winners will be announced next week, on June 25th in London. In advance of the ceremony, we asked the finalists to introduce their shortlisted books in their own words. Read on to find out what they had to say.

Orwell Prize shortlist reading: subscribers go free

Our shortlist readings continue tomorrow at Foyles, London, where finalists Mishal Husain (Broken Threads) and Simon Parkin (The Forbidden Garden of Leningrad) will be in conversation with Orwell Prize judge Thangam Debbonaire.

We’re delighted to be able to offer newsletter subscribers a free ticket. Simply reply to this email with your name and email address to secure yours.

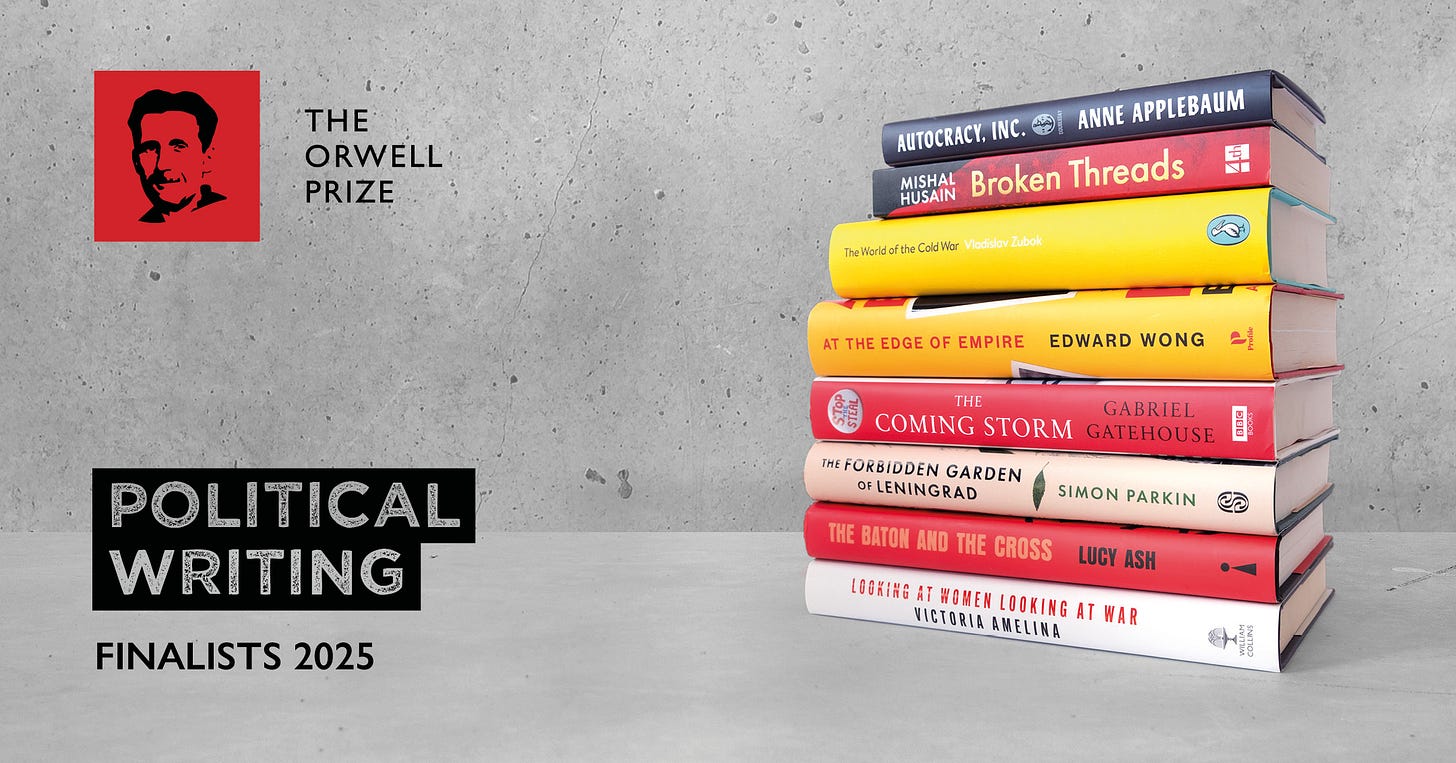

Political Writing

Anne Applebaum, Autocracy, Inc.

Autocracy Inc describes a network of modern dictatorships, united not by ideology, but by interests. Their most important goal is to undermine the language and the ideas of the democratic world, since that is the language of their own political opponents. Towards that end, they use money, weapons and propaganda in similar and overlapping ways.

Lucy Ash, The Baton and the Cross

My book is the story of Orthodox Christianity in Russia - I wrote it to try and understand why the country’s top cleric, Patriarch Kirill, is complicit in one of the darkest chapters of Russian history. And I realised his hawkishness is nothing new - a poisonous co-dependency between church and state has existed for centuries.

Edward Wong, At the Edge of Empire

At the Edge of Empire tells the epic story of modern China, a nation whose transformations are shaping the world unlike any other. My book brings the reader on this journey through braided narratives: that of my father serving in Mao’s army in pivotal regions of China in the1950s, and that of my own quest to understand the nation as a correspondent reporting there for The New York Times for nearly a decade starting in 2008. While living in China, I also sought to investigate my father’s mysterious past in the military, and this book unveils those family secrets.

Mishal Husain, Broken Threads

Broken Threads uses a family story - my own family story - as a way to humanise, explain and contextualise a moment in history that British foreign policy has glossed over through the decades. It’s about how the division of South Asia - with consequences including a nuclear arms race in the region - is inextricably linked to British politics from the First World War onwards. There is a stark contrast between the effort put into keeping India within Britain’s purview, for generations, and the half-hearted and limited attempt to find a former of post-Raj government that would have cross-community consent. The political also becomes personal, as the two most senior British officials in India disagreed and ultimately, Mountbatten forced General Auchinleck out.

Victoria Amelina, Looking at Women, Looking at War

answered by her friend, Sasha Dovzhyk

While Victoria Amelina did not survive in a Russian missile strike, her words did: “Since the war began in 2014, and with the full-scale invasion now, I, along with millions of my fellow citizens in Ukraine, have been in search of one thing: justice. The quest for justice has turned me from a novelist and mother into a war crimes researcher. […] I’ve done this to uncover the truth, to ensure the survival of memory, and to give justice and lasting peace a chance. This same urge also slowly turned me back into a storyteller.” This book is Victoria’s testimony.

Simon Parkin, The Forbidden Garden of Leningrad

The Forbidden Garden of Leningrad tells the story of the men and women who protected the world’s first seed bank during the longest blockade in recorded human history. In 1941, as food stocks in the city ran dry, the botanists were called to defend a collection of valuable seeds drawn from around the world. Almost everything was edible, and the quarter of a million could have sustained the botanists for months. And yet, to consume these specimens would have felt like a betrayal of the past two decades’ worth of efforts. They were faced with a fundamental dilemma: to save a collection designed to eradicate famine, or to use it to save themselves.

Gabriel Gatehouse, The Coming Storm

The Coming Storm tells the story of how conspiracy culture captured American politics, and how changes in communication technology are driving an epochal shift the likes of which we haven’t seen since the end of the feudal period.

Political Fiction

Natasha Brown, Universality

Universality begins with a magazine exposé that’s gone viral. It’s written in the “long-read” article style — pulpy, fast-paced, scandalous — and it promises to get to the truth behind a mysterious attack. The rest of the book digs into the messy aftermath of that viral exposé. Each chapter dives into a different perspective from one of the mystery’s key players, revealing the murky uncertainty of any single, shared ‘truth.’ This is a book that’s deeply interested in the ways that people talk and write – and how the lines between truth and fiction, or real life and entertainment, can become blurred. It’s also about a man being bludgeoned with a solid gold bar. I’d say it’s like Knives Out meets Roland Barthes.

Noah Eaton, The Harrow

The Harrow is the last of the muckraking magazines in London to have survived the great culling of local journalism by the internet. Run by the eccentric John Salmon, who carries a multitude of chips on his shoulder, its investigation of a gang killing leads to a confrontation with the powerful leader of the local council and to the brink of extinction.

Donal Ryan, Heart be at Peace

Heart, be at Peace is set in the summer of 2019 in rural Ireland, as tensions between the citizens of a small town and local drug dealers flare and combust. It’s a follow-up to my debut novel, The Spinning Heart, and has the same polyphonic form, comprising twenty-one linked monologues

Elif Shafak, There are Rivers in the Sky

There Are Rivers in the Sky is the story of a tiny raindrop that journeys through time and geography, a love letter to water. I say this as a writer with deep emotional ties to the Middle East. Of the most water stressed nations today seven are in the Middle East and in North Africa. Our rivers are dying. This has massive consequences for everyone, but particularly for women, children and the poor. This novel brings together three characters who are different at first glance, but who are deeply, surprisingly connected. Then, two rivers that are close to my heart: the Thames and the Tigris. And one ancient poem: The Epic of Gilgamesh. Three, two, one… and everything is connected via a single drop of water.

Jo McMillan, The Accidental Immigrants

The Accidental Immigrants is about what happens when you suddenly find yourself an unwanted foreigner. It’s about the xenophobia gripping the globe and what it’s like to be caught up in it. The story follows a British couple as they’re swept up in a far-right landslide, targeted as immigrants, endangered, and desperate to get out. But there’s also the problem of getting into Britain and navigating Home Office rules. Punctuated with UK Immigration procedures and with endnotes that reveal the truth behind the fiction, this story is both allegory and warning.

Making sense of chaos: finalists on why they write

In his essay Why I Write, George Orwell claimed that prose writers have four ‘great motivations’ (putting aside the need to earn a living): sheer egoism; aesthetic enthusiasm; historical impulse; and political purpose. Head to LitHub to read the finalists’ own answers to Orwell’s question. Why do you write?