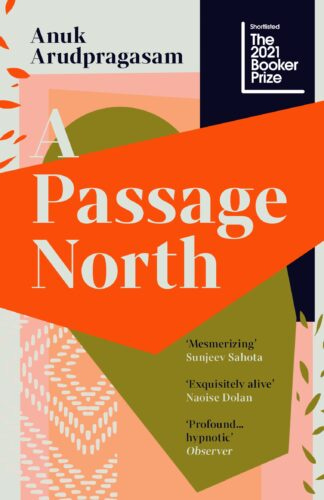

A Passage North

'A poignant exploration of the unattainable distances between who we are and what we seek.'

It begins with a message: a telephone call informing Krishan that his grandmother's former caregiver has died. As Krishan makes the long journey by train from the Sri Lankan capital into the war-torn Northern Province for the funeral, so he travels into the soul of a country devastated by civil war.

Written with precision and grace, A Passage North is a luminous meditation on time and consciousness, race and national identity, and a poignant exploration of the unattainable distances between who we are and what we seek. We are delighted to share this exclusive extract from Anuk Arudpragasam’s latest novel, a finalist for The Orwell Prize for Political Fiction.

The Orwell Prizes for Political Writing and Political Fiction 2022 shortlists, released last month, highlight the finest politically engaged books published in 2021. To see the lists, visit our website here.

The present, we assume, is eternally before us, one of the few things in life from which we cannot be parted. It overwhelms us in the painful first moments of entry into the world, when it is still too new to be managed or negotiated, remains by our side during childhood and adolescence, in those years before the weight of memory and expectation, and so it is sad and a little unsettling to see that we become, as we grow older, much less capable of touching, grazing, or even glimpsing it, that the closest we seem to get to the present are those brief moments we stop to consider the spaces our bodies are occupying, the intimate warmth of the sheets in which we wake, the scratched surface of the window on a train taking us somewhere else, as if the only way we can hold time still is by trying physically to prevent the objects around us from moving. The present, we realize, eludes us more and more as the years go by, showing itself for fleeting moments before losing us in the world’s incessant movement, fleeing the second we look away and leaving scarcely a trace of its passing, or this at least is how it usually seems in retrospect, when in the next brief moment of consciousness, the next occasion we are able to hold things still, we realize how much time has passed since we were last aware of ourselves, when we realize how many days, weeks, and months have slipped by without our consent. Events take place, moods ebb and flow, people and situations come and go, but looking back during these rare junctures in which we are, for whatever reason, lifted up from the circular daydream of everyday life, we are slightly surprised to find ourselves in the places we are, as though we were absent while everything was happening, as though we were somewhere else during the time that is usually referred to as our life. Waking up each morning we follow by circuitous routes the thread of habit, out of our homes, into the world, and back to our beds at night, move unseeingly through familiar paths, one day giving way to another and one week to the next, so that when in the midst of this daydream something happens and the thread is finally cut, when, in a moment of strong desire or unexpected loss, the rhythms of life are interrupted, we look around and are quietly surprised to see that the world is vaster than we thought, as if we’d been tricked or cheated out of all that time, time that in retrospect appears to have contained nothing of substance, no change and no duration, time that has come and gone but left us somehow untouched.

Standing there before the window of his room, looking out through the dust-coated pane of glass at the empty lot next door, at the ground overrun by grasses and weeds, the empty bottles of arrack scattered near the gate, it was this strange sense of being cast outside time that held Krishan still as he tried to make sense of the call he’d just received, the call that had put an end to all his plans for the evening, the call informing him that Rani, his grandmother’s former caretaker, had died. He’d come home not long before from the office of the NGO at which he worked, had taken off his shoes and come upstairs to find, as usual, his grandmother standing outside his room, waiting impatiently to share all the thoughts she’d saved up over the course of the day. His grandmother knew he left work between five and half past five on most days, that if he came straight home, depending on whether he took a three- wheeler, bus, or walked, he could be expected at home between a quarter past five and a quarter past six. His timely arrival was an axiom in the organization of her day, and she held him to it with such severity that she would, if there was ever any deviation from the norm, be appeased only by a detailed explanation, that an urgent meeting or deadline had kept him at work longer than usual, that the roads had been blocked because of some rally or procession, when she’d become convinced, in other words, that the deviation was exceptional and that the laws she’d laid down in her room for the operation of the world outside were still in motion. He’d listened as she talked about the clothes she needed to wash, about her conjectures on what his mother was making for dinner, about her plans to shampoo her hair the next morning, and when at last there was a pause in her speech he’d begun to shuffle away, saying he was going out with friends later and wanted to rest a while in his room. She would be hurt by his unexpected desertion, he knew, but he’d been waiting all afternoon for some time alone, had been waiting for peace and quiet so he could think about the email he’d received earlier in the day, the first communication he’d received from Anjum in so long, the first attempt she’d made since the end of their relationship to find out what he was doing and what his life now was like. He’d closed the browser as soon as he finished reading the message, had suppressed his desire to pore over and scrutinize every word, knowing he’d be unable to finish his work if he let himself reflect on the email, that it was best to wait till he was home and could think about everything undisturbed. He’d talked with his grandmother a little more—it was her habit to ask more questions when she knew he wanted to leave, as a way of postponing or prolonging his departure—then watched as she turned reluctantly into her room and closed the door behind her. He’d remained in the vestibule a moment longer, had then gone to his room, closed the door, and turned the key twice in the lock, as if double- bolting the door would guarantee him the solitude he sought. He’d turned on the fan, peeled off his clothes, then changed into a fresh T-shirt and pair of shorts, and it was just as he’d lain down on his bed and stretched out his limbs, just as he’d prepared himself to consider the email and the images it brought to the surface of his mind, that the phone in the hall began to ring, its insistent, high-pitched tone invading his room through the door. He’d sat up on the bed and waited a few seconds in the hope it would stop, but the ringing had continued without pause and slightly annoyed, deciding to deal with the call as quickly as possible, brusquely if necessary, he’d gotten up and made his way to the hall.

Anuk Arudpragasam is a Sri Lankan Tamil novelist. His first novel, The Story of a Brief Marriage, was translated into seven languages, won the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature, and was shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize. His second novel, A Passage North, came out in July 2021.