'Coming Up For Air' with Richard Blair

A conversation with Orwell's son, Richard Blair, in Marrakech.

In November 2023, The Orwell Youth Prize Programme Coordinator, Tabby Hayward, visited Morocco with the Orwell Society, to follow in George Orwell’s footsteps. Orwell’s son, Richard Blair, kindly answered some questions about his father and mother’s time in Marrakech. You can listen to the audio recording and read the transcript below.

Tabby Hayward in conversation with Richard Blair. Photo by Alastair Blair

Tabby: So I thought I'd just start at the beginning. Why did your father and mother come to Marrakech?

Richard: Well, it was due to the fact that in 1937 or so, after he'd come back from Spain, he developed TB. And he had been to a place called Preston Hall in Kent at the behest of his brother in law. And he was given some, at that time, some money anonymously, to go and have a holiday somewhere warm. And Marrakech was the place that both my father and my mother Eileen decided upon. And this is where they came to, via Casablanca, and ended up in Marrakech.

Tabby: And did they ever find out who the anonymous benefactor was?

Richard: Many, many years later. It was Michael Myers, and he (Orwell) did repay him, oh crikey, I think it was somewhere around about 1945. But at that time, it was anonymous. And I guess they were grateful for it.

Tabby: And how was your father's, and your mother's, health at the time then, if that was the main reason they came to Morocco?

Richard: Father's health was not terribly good. He'd been wounded in Spain. He'd been treated for TB. And of course, in those days they didn't have the antibiotics that we have nowadays. And he came here, and I think there was a lot of grumbling and muttering and he did complain a bit but did he enjoy it, the experience on the whole? I suppose he did. I think my mother probably did. She would send off some quite ribald letters back to her friend, Nora Myles, about the flies and the coffins and the dead bodies. And you know, every time he was sitting in a restaurant, the flies would dash out when the coffin went past, and then all come back again, in about five minutes.

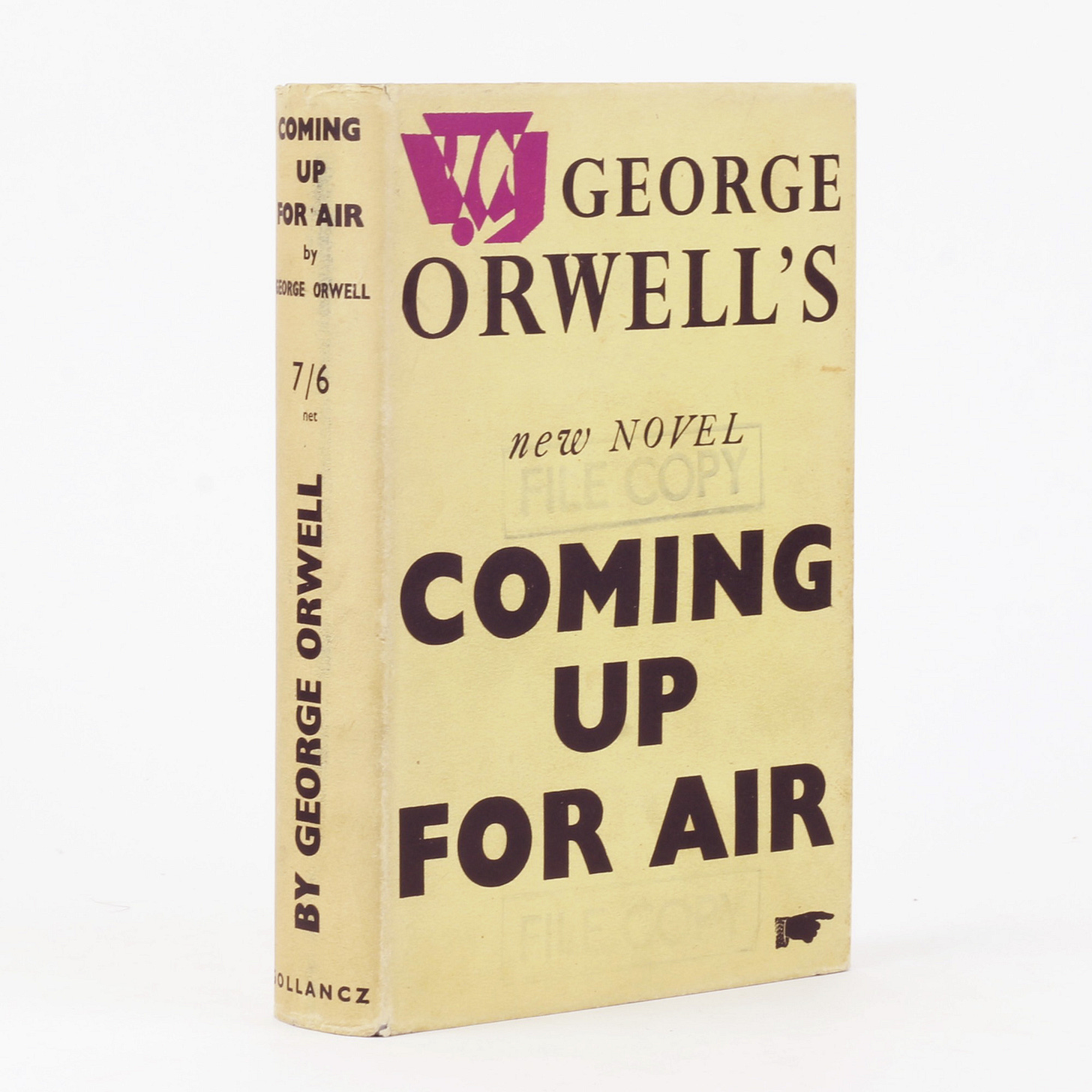

They (Orwell and Eileen) did move about a little bit, they went up into the Atlas Mountains, and spent a week up there. And I think they probably enjoyed that. I hope that they enjoyed the experience. I think my mother probably did more so than my father, but he busied himself, writing Coming Up For Air.

Tabby: On this trip is there a site, a place that we're going that you're particularly interested to see or experience?

Richard: Well, we're going to go and see various places where they stayed briefly. But the actual site where the bungalow (Villa Simont) was that they lived in for (most of) the period of time they were here, no longer exists. But we have defined it down to a very small area of probability. And so I guess that is going to be the place of homage, as it were.

Tabby: And how do you think it will feel, or do you think it will be an emotional experience, to see it?

Richard: Yes of course it will, it's a pilgrimage for me, personally speaking.

Tabby: You mentioned Orwell moved around a lot, over the course of his life. And I was interested, as the Orwell Youth Prize theme this year is about home - I wondered, do you have a sense of where home was for your father?

Richard: That's quite a difficult question. I'm not sure, because he died so young. I think, had he survived his TB in the 40s, in the late 40s, I think Jura would have been his, I would like to have thought that Jura would have been his base, from which he would then go to other places, but always come back to his island in the Hebrides.

Tabby: And still on that theme of home, he wrote Coming up for Air while he was staying in Morocco, and to read the novel, you don't get an immediate sense that he was far away from England. It's such an English novel…

Richard: He was a patriotic man, in spite of what he may have written. He'd like to have a crack at most people. Ultimately, it would come back to the fact that he was a patriot and he would fight for his country, in spite of the many things he may have said.

Tabby: Do you think that being away from England helped him to write some of these things and realise that sense?

Richard: I’m not sure! I think he grumbled quite a lot while he was here, but Eileen sort of just put up with it. I think her health wasn't – was probably okay, in those days. I think she probably may have had some underlying problems which she slightly ignored. It wasn't too serious – well at that time wasn’t too serious, but which turned out to be so later on, in the first half of the war.

Tabby: Do you have any favourite anecdotes or moments from the diaries about their time here? I know you mentioned yesterday about the Japanese red bicycle. Are there any stories that stand out to you?

Richard: So the Japanese red bicycle, which my mother bought to cycle in from the bungalow into town…Why a red Japanese bicycle, I'm not quite sure! And I guess that the funniest bit really is Eileen’s letter to Nora Myles, about when you're sitting in a restaurant, which is inhabited by flies. And every time a corpse went past, the flies vacated the restaurant, only to come back again five minutes later. I think it kind of sums it up. Because my mother was actually very funny, very dry sense of humor, like my father. And I think this is missed by so many people. People think, Oh, she's complaining. She's not, she's having a quiet dig at my father. She knew perfectly well, what my father was like, and she accepted him for what he was. Alright, she gave up her career. But I think she saw my father as someone who was probably – I mean, they were equal, intellectually speaking. But she thought, no, I'll let him. And it was the mores of the day, that a wife tended to allow the husband to be the patriarch, the breadwinner, call it what you will. And I think she probably quite, I don't know, I think probably she was quite willing to step aside and let him carry on. Which has been misinterpreted time and time again.

Tabby: It’s interesting, the note that you mentioned about in her letter saying about the flies, coming to the table, and then going away, and then coming back later, that comes into Orwell’s essay ‘Marrakech’, doesn’t it? So you can see them inspiring each other?

Richard: Yes, that's right. On balance, I'm not sure that he (enjoyed his time in Marrakech). He found the heat oppressive. I think he disliked the way that the local people treated their animals. You know, the poor old donkeys were just worked to death until they dropped dead literally where they stood. And he didn't understand the way the local people worked and their philosophy, any more than they would have understood his philosophy about animals because he was very much into nature. He liked his animals very much, of course, as we know, from previous books, and life in Wallington with his goats and so on, so forth. And they had goats, when they were here. And they tried to create a garden, and cultivated bits and pieces.

Tabby: So they were making a home?

Richard: They were trying to make a home! Which they were never going to keep. But it was something to do. And if you read the letters, it's surprising how often he was ill. His chest would then - it wasn't just a question of a few days of not doing anything. It was a whole fortnight of not doing anything. A lot of time was spent not doing very much.

I think they enjoyed the trip up into the Atlas Mountains. Very much.

Tabby: I just wondered if you had any words of encouragement or advice for young writers who might be entering the prize this year, or any bits of Orwell’s writing they should have a look at?

Richard: I suppose my advice would be, as it always has been, is Orwell had a great deal to say about an awful lot of things with a great deal of common sense. That is, common sense, clarity of thought. And I think don't be frightened to say what you want to say. As we know from his essay about why I write, the six rules of English, but the sixth one was break any of these rules, but don't say anything absolutely outrageous.

Tabby: Yes. That's good advice in general, I think, for all writers!

Richard: I think so! It should be pinned to the wall of every public building in the country.

Great interview Richard and Tabby.

The benefactor was wealthy Old Etonian, friend and admirer of Orwell, Leopold Hamilton (L.H.) Myers (1881-1944). It was intended as a gift, but Orwell insisted on repaying what he regarded as a "debt" through intermediary Dorothy Plowman in 1946 (sadly after Myers had taken his own life).

Enjoyed very much. Thank you