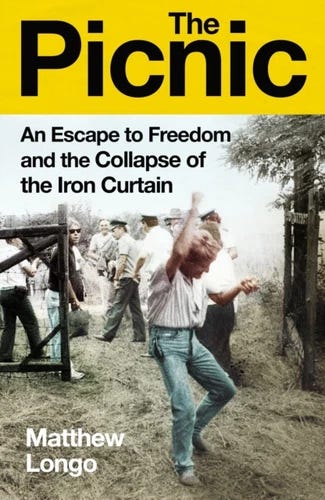

Today, we’re delighted to share an essay by Matthew Longo, winner of The Orwell Prize for Political Writing 2024 for his book “The Picnic”, a gripping reconstruction of the daring escape to freedom of hundreds of East Germans in the summer of 1989. We asked Matthew to share some thoughts on winning The Orwell Prize: the result was a profound reflection on the act of writing - and the role of “unsurety” in George Orwell’s work.

Imposter! Reflections on The Orwell Prize - Matthew Longo

Being called to a podium to speak is a strange, isolating experience, even when the occasion is a happy one. After the rush of excitement at being awarded the Orwell Prize and the flat-footed shuffle down the aisle, my mind clouded with doubts – a medley of sentiments often termed imposter syndrome. After all, what book could possibly warrant such an accolade?

The proceedings set high expectations. Most poignant was the award for reporting on homelessness. The winners had been homeless themselves and spoke with a clarity and humanity rarely seen in political discourse. Theirs was a plea for compassion. To be recognized as human, with all the redemptive potential inherent to that condition. The political climate also pressed in: the war in Gaza was in its ninth month and images of brutality and murder flooded newsfeeds. At the prize proceedings a further aspect of the conflict came to the fore: the horrific number of Palestinian journalists who had been killed trying to report the news. These were the real heirs to Orwell, brave people who faced down tanks and bombs to tell the story of Palestinian lives, so often disregarded.

After the Prize ceremony, the question of imposter-hood frequently returned to mind. It is something I think most writers identify with. When did these doubts creep in, I wondered, and did they affect my book? With the benefit of hindsight, is there anything I would have changed?

In September 2018 I had a conversation with Miklós Németh – the last communist Prime Minister of Hungary – in the hills surrounding Lake Balaton. Németh was a pro-democracy advocate in the 1980s and an important force behind the political changes that would ultimately bring down the Berlin Wall. I took notes assiduously as we spoke about the end days of the Cold War, eating almonds on his veranda as the early autumn sun set upon us. Yet one thing he said that day didn’t make it into my book, The Picnic. I realize now it should have.

After we had run through the triumphant events of 1989, our conversation turned to its aftermath. Németh had been active in the transition, lobbying western governments for redevelopment funds so the eastern states would be less susceptible to depredation by the stronger economies of the west. Specifically, Németh advocated for a second Marshall Plan to rebuild the former Communist Bloc, modeled on the one which rebuilt Europe after World War II. This wouldn’t just be helpful for the east, Németh counseled, but would be better for the west too. In making his case to a high-ranking US official, Németh summoned a quote by French economist, Alfred Sauvy:

“If the money doesn’t go where the people are, the people will go where the money is.”

Listening to Németh recall this encounter, I immediately felt the force of his advice. From the vantage of today, it’s hard to take the same triumphant view of 1989 as we once did. Across the west our societies are beset by creeping authoritarianism, xenophobia, and skyrocketing inequality. How did we get from the revolutionary promise of 1989 to this fractious present? And might the roots of our disfunction stem back to that very moment of freedom once celebrated?

Németh was an economist before he became a politician; like many who climbed the communist ranks in Hungary, he had studied at the Karl Marx University in Budapest. Later he received a fellowship to study at Harvard. Having been educated in both the east and west, Németh understood what transition would mean in ways others didn’t: the west was not the liberal utopia envisaged by many of his fellow reformers; nor was it the amoral hellscape of communist propaganda. In fact, both systems were fraught in manifold (if different) ways. Regrettably, Németh’s plan for a new Marshall Plan didn’t obtain; after the fall of the Wall, the west quickly pivoted to other issues.

Speaking about transition today, Németh’s expression sours. What so upsets him isn’t just that Hungary struggled to find its footing after the change of systems, but that he had foreseen what this would mean for liberalism broadly. Because the western states didn’t rebuild the economies of the east, people across the east went looking for work in the west (‘where the money was’). This meant a rise in immigration but also, as Németh anticipated, a corresponding era of xenophobic, illiberal politics (often given the omnibus name “populism”). He tried to warn western officials, but no one heeded his call.

Books take many years to write; naturally things get lost along the way. In the end, although I treat most of these issues, I did not mention Németh’s anecdote about Sauvy. It was something I agonized over. Had Németh really said these words in 1989? The anecdote was hard to substantiate, so I left it out. And yet, these days I often find myself retelling it. Each time, I am consumed by regret. Németh felt Sauvy’s adage held the clue to how 1989 would shape our world. Increasingly, I think he was right.

It would be easy to conclude something overarching about being awarded the Orwell Prize: that it has inspired me to have courage in my convictions, for example. But this would be nonsense: writing is an inherently lonely experience, overshadowed by doubt. Instead, I increasingly feel the opposite is true: insecurities in writing are a good thing; we ought to be open regarding what we don’t know or don’t feel certain about. This is what forces us to grapple with moral and political touchstones, tricky issues about which we are ourselves unsure; to highlight evidence we think might be important, even if we aren’t exactly sure why. Here I take a page from Orwell himself, a master of this kind of narration; the writer who figures things out as he goes along.

Take for example Orwell’s, Shooting an Elephant (1936), which details his experience as an officer of the British Empire in Burma, called upon to handle a crisis of an elephant gone mad. Orwell takes as his starting point the insecurities he feels about his position, wedged between two entities he finds disagreeable: the British Empire from which he takes orders, and the subjects over whom he rules (who despise him and whom he in turn despises). The essay is written later, after Orwell is back from Burma, a temporality which casts his prior ignorance into relief. “[The situation] was perplexing and upsetting,” he writes. “I could get nothing into perspective.”

Orwell’s unsurety only increases when the time comes to address the elephant. “A story always sounds clear enough at a distance,” he writes, “but the nearer you get to the scene of events the vaguer it becomes.” He arrives to find the circumstances murky and information countervailing, a social and psychological ecosystem in which he would be forced to perform the very authority he found distasteful. Orwell quickly realizes that he will have to shoot the elephant, compelled forth not by some physical force but his own concerns over “looking and feeling a fool.”

From this experience, Orwell draws out a powerful reflection on empire: that it is comprised of scores of people like him, forced into acting brutally by the nature of their office. That the hierarchy of power leads both governor and governed into positions that beget and legitimate violence beyond what either would intend. In this small story, this means killing an elephant; for Orwell, it means appreciating the limitations of his station.

“[It was at this moment] that I first grasped the hollowness, the futility of man’s dominion in the East. Here was I, the white man with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native crowd – seemingly the leading actor of the piece; but in reality I was only an absurd puppet pushed to and fro…”

Orwell’s essay begins as a story of authority and ends with impotence and doubt. By foregrounding his own unsteadiness, he invites readers to stand beside him, to think through how they might have behaved given those same uncertainties. To consider the emotions and fears that govern our actions, even when we wish they didn’t or pretend they don’t.

The world is unimaginably complex, our interpretations constrained. To write well about politics – especially events that took place in the past – it is important to accommodate a degree of insecurity in one’s voice and embrace the partiality of one’s knowledge: what we might have misread, misheard, misremembered; what we scribbled illegibly, or forgot to write down. This doesn’t just mean expressing what we don’t know – history is of course an incomplete puzzle – but that even what we do know is filtered through our positionality, as Orwell shows us. And indeed, when I think back upon my own book, it is this narrative posture that I am most proud of.

Returning to Németh, I think this helps explain my regret: throughout the book, I had developed precisely the voice that could have sustained the uncertainty of the anecdote. Sure, it is possible that his reflection was an ex-post rationalization; I treated many of his remarks this way. In our memories, we often act more nobly, more morally, than we ever did in life. But this is exactly why we should be upfront about the details we agonize over. By putting our thoughts on the page, we empower readers to come to their own conclusions; omitting that material simply boxes them out. Navigating uncertainty is precisely what I tried to do with Németh’s anecdotes – all, that is, except one.

What then did I learn from the Orwell Prize? That I should be proud of the book, despite my regrets. But also that insecurities are important. Perhaps, it is good to feel like an imposter after all.

Matthew Longo is assistant professor of political science at Leiden University. He is the author of two books: The Picnic: A Dream of Freedom and the Collapse of the Iron Curtain (W. W. Norton, 2023) and The Politics of Borders: Sovereignty, Security, and the Citizen After 9/11 (CUP, 2018).

This essay was published in The Orwell Prize Anthology 2024. As well as supporting our work promoting Orwell’s legacy, Friends of the Foundation receive an annual copy of our anthology, complimentary tickets to our live events and more.