On Friday 26th November 2021, Ian McEwan delivered the Orwell Memorial Lecture on 'Politics and the Imagination: Reflections on Orwell's Inside the Whale'. The Orwell Youth Fellows were invited to attend and prepared the first two questions, one of which was asked by Jennifer Yang. Jennifer has written the following piece as a response to Ian McEwan's lecture.

The noise of the crowd gradually died down. In a few seconds I would see Ian McEwan, the man himself, speaking to us about politics and imagination. Such are the lofty themes that hover over our heads! Meeting Ian McEwan had always been my dream. It’s one of those dreams that you leave at the bottom of your heart because you don’t think it will ever come true. Two years ago, when I finished Atonement, I instantly wrote in my diary, ‘I LOVE ATONEMENT! It fills me with the ecstasy of growing up but also tinges me with a dint of fear. Why is there so little time for joyousness but so much for suffering?’ Little did I know I would eventually meet Mr. McEwan in person and he would laugh and say, ‘Pessimism is delicious.’

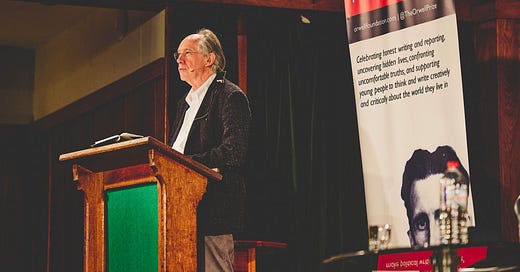

Conway Hall. Excited chatters of the crowd filled the antiquated lecture room. And there he was, the omniscient master of words, the conjurer of those alien yet familiar realms, standing rather seriously. But he was there, his presence a commanding authority.

‘Camus quotes Andre Gide,’ McEwan said, ‘ “Art lives on constraint and dies of freedom”. The constraint Gide refers to does not come from the outside, from government censors or compliant editors. The possibilities of art in turbulent, dangerous times, Camus writes, lies in “our courage and our will to be lucid”. The more chaotic and threatening the world, the more disordered his material, Camus insists, so greater order is needed in the art – “the stricter will be his rule and the more he will assert his freedom”’.

Then, think about the courage it takes for a writer to believe in the power of her words – the supposition that her words could impose some sort of order amongst all the other misused and misunderstood words! It means putting one’s belief out there, in a world filled with dissent and malice. If the purpose of an author is to, according to Camus, ‘prevent the world from destroying itself’, then how urgent would authors feel to rescue the world from its own flames? How dejected would they feel if they realise their writing cannot steer the direction our stampede of society is heading in? Will they cast their pens away, or will they proceed?

Perhaps pessimism is the solution. McEwan said George Orwell ‘abandoned himself and freed himself completely within an all-encompassing pessimism.’ This slightly oxymoronic phrase troubled me for a long time, and I question myself from time to time, ‘is there such a thing as beauty in the spirit of the defeated?’ Could there be a silent revolution? Perhaps sometimes silence is the only way to defend one’s will to disengage in human activities, as in this way the author reduces himself to a cipher, helpless yet undemanding of pity. For what is more moving, a man fuelled miraculously with undefinable hope in the bleakest time of human civilisation, or one that has surrendered, completely and unabashedly? I would say it’s the latter. The act of surrendering is terrifying – it symbolises utter exhaustion. We can no longer lie on the sofa in our living room and shrug and say, ‘someone will go and save the polar bear’ – our authors tell us the ‘someone’ we are constantly referring to has perished. Thus, one might choose to do something about this colossal global issue - the climate crisis, in this case- starting from something right in front of one's nose.

***

I have never thought of the world in that way before – it’s full of contradictions. Paradoxically, writing is the sole act that denotes optimism. Creating a defeated character does not mean that the author has put his arms up into the air. It is, in fact, the opposite. One must be writing with a clear intention in mind, and writers know themselves to be inventors of a new world, both in their works and through their works. So, in the end, there is still hope – built on selfless inventors who dwell unyieldingly in formidable solitude.

Then, am I ready? McEwan was quoting Matsuo Bashō: ‘The old pond/ A frog jumps in -/The sound of the water’. He was linking a 17th century haiku to present-day climate change, turning the death of an insignificant four-legged amphibian into an alarming sign. Strange how frogs and, in Orwell’s case, toads tell us so much about the world around us. To Bashō and Orwell they signify political quietism, in a time when ponds were neither flooded nor discharged with human waste. In our time, having the time and solitude to appreciate a frog in the middle of a pond seems like a luxury.

I was leaning forward, aware of every breath I blew into my mask. McEwan started with Orwell, moved to Miller, to Joyce, to James, to Camus, and now to Bashō, a poet from the Far East whose home is only a stretch of sea away from mine; McEwan moved from World War II to the present day, peering somehow anxiously into the future. And there was Orwell, smirking mysteriously in the background on the poster, either deriding our formidable stupidity or lauding our formidable intelligence. Somehow words have plodded their way through calamities. In the end, we still have storytellers, boldly documenting their world, our world, the world we share. Writing is a form of rebirth.

Jennifer Yang was a junior winner in the 2021 Orwell Youth Prize, with her piece 'On Keeping a Time Capsule' and is currently an Orwell Youth Prize Fellow.

The Orwell Memorial Lecture by Ian McEwan, on 'Politics and the Imagination: Reflections on Orwell's Inside the Whale', is available to watch below.