My Fourth Time, We Drowned: Author update

One year on from winning The Orwell Prize for Political Writing, Sally Hayden updates the story

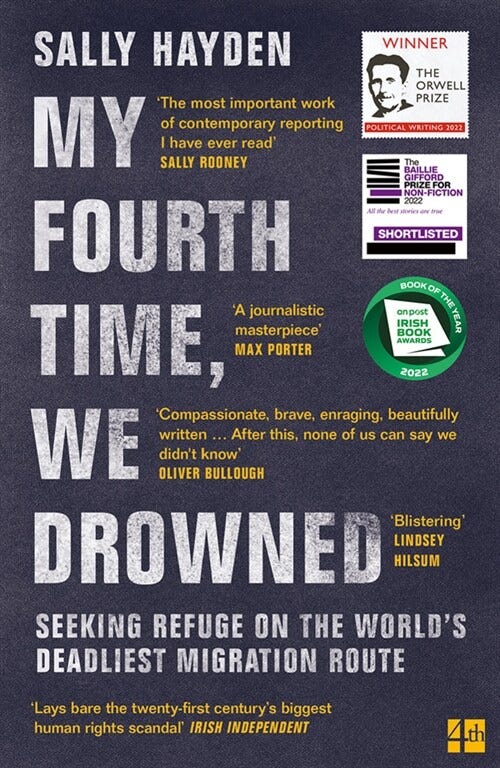

On the 14th July 2022, the Irish journalist and writer Sally Hayden was awarded The Orwell Prize for Political Writing for her debut book My Fourth Time, We Drowned, an investigation into the migrant crisis across north Africa and into Europe. A version of the following update was included in the paperback edition in March of this year.

Author update

Just over one month before My Fourth Time, We Drowned appeared in bookshops, Russia invaded Ukraine. We had already gone to print, so that war is not mentioned in the original text. When I began doing interviews to publicise the book, though, I was asked about it every time.

What happened next had surprised me and everyone else I knew who reported on European migration policy. The EU, miraculously, kept its borders open. In the first ten days after the invasion began more than 1.5 million Ukrainians crossed into Europe. Within seven months that number would top seven million – drastically higher than the 1.3 million that claimed asylum in the EU in the whole of 2015, the year of the so-called ‘European migrant crisis’.

For the first time the EU invoked the temporary protection directive, which saw Ukrainian refugees granted immediate residency rights, the chance to work, social welfare assistance and a range of other supports. In my birth city, Dublin, staff manned booths, issuing social security numbers to Ukrainians before they even left the airport. This made it clear to me, and many others, that a more empathetic migration policy had been possible all along. Some colleagues said it gave them hope that the situation would now improve for everyone. For many refugees and migrants who had been through horrific journeys in Libya and elsewhere, where they were met with pushbacks, torture and abuse, the reception given to Ukrainians was confronting. ‘It’s just racism,’ said one source, about the vast difference in the way he had been treated.

Two weeks after this book was published, I stood in a displacement camp in southwest Somalia. The Horn of Africa country was experiencing a historic drought. Three rainy seasons had failed, and a fourth was about to. In front of me were hundreds of displaced people who had been loaded off trucks with nothing but the clothes they were wearing. Mothers told me about lengthy walks to find transport; how their children had died en route and were buried at the side of the road. I walked among dozens of goat carcasses: the final remains of herds of livestock which had sustained generations of Somali nomads, before they were wiped out by thirst and hunger. On a second trip, I counted 101 graves inside another Somali displacement camp. All belonged to children.

The drought was said to be the result of climate change, yet Somalia’s emissions are a tiny percentage of those emitted by rich world countries. Ireland, despite having a population of only around one-third of Somalia’s, produces fifty times more emissions; the UK five hundred times more; and the US nearly seven thousand times more.

Somalis arrived, in their tens of thousands, to the small pockets of land where international organisations had a presence. By August last year one million had been displaced nationwide. Still, I witnessed no food distributions until I visited a local trader to discuss the implications of the Ukraine war and soaring fuel prices. In front of his shop were dozens of plastic bags filled with rice and other supplies. He told me that they were put together using money sent by the Somali diaspora: people with jobs in Europe or the US who transferred cash directly back home. It made me think how allowing safe migration can be a form of foreign aid, and a much more effective one than donations distributed through international aid organisations, which have huge overheads and are often accused of perpetuating a host of other systemic issues.

***

My Fourth Time, We Drowned was originally published in March 2022.

In April, Fabrice Leggeri, the head of EU border agency Frontex, resigned amid increased allegations that the agency had been violating human rights. In his resignation letter, Leggeri complained that his mandate had ‘silently but effectively been changed’. His standing down was a momentous chance to re-evaluate the role of the agency and the way it operates, but the European public did not seem to be paying attention.

That same month, the International Criminal Court’s prosecutor’s office said, for the first time, that it had made a preliminary assessment that the abuses happening against refugees and migrants in Libya - which I had documented - may constitute crimes against humanity and war crimes.

In August 2022, the milestone of 100,000 interceptions by the Libyan coastguard as a direct result of EU policy was passed. There was no fanfare, no public commotion. I also noticed no outcry when the number of men, women and children who drowned or went missing in the Central Mediterranean since 2014 topped 20,000 (the number who died or went missing across the whole Mediterranean Sea, for the same period, surpassed 25,000).

In November, eight months after its publication, the book was cited in a submission to the International Criminal Court, which was prepared by the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights. It finally called for named European politicians and EU officials to be prosecuted. It also said that the interceptions at sea and the return of people to Libya constituted a crime against humanity. The identified alleged ‘co-perpetrators’ included former EU foreign affairs chief Federica Mogherini; former Italian Interior Ministers, Marco Minniti and Matteo Salvini; the current and former Prime Ministers of Malta, Robert Abela and Joseph Muscat; and Leggeri, the former head of Frontex.

In the UK, anti-migration sentiment seemed to be reaching new highs. In April 2022, the British government announced its plan to begin deporting asylum seekers to Rwanda. This came a few months after its Home Office sent staff to Gashora camp, where Libya evacuees were staying: the same camp that I was refused access to. There was serious money in the deal for the Rwandan government, with the UK pledging a 120-million-pound initial payment.

The first deportation flight was scheduled for June, but it was cancelled at the last minute, pending a legal challenge. This was not before men were forced onto a plane, with at least one strapped into a restraining harness. My experience reporting in Rwanda, much of which is documented in the book, was submitted as evidence in the legal challenge taken against the government. That first challenge failed, before a court of appeal recently ruled the deportations unlawful.

***

I was invited to present my findings in the Irish parliament. I did an online event with a British lord, and briefings for many different charities and NGOs. I spoke to more current and former politicians, diplomats and EU advisors. Generally, political figures would tell me the same thing: that I had made a valiant effort to collect evidence of wrongdoing, but the European public does not care about Africans, or about black refugees and migrants. If politicians acted against the status quo, they would be voted out at the next election – and what good was that? They needed the general public to care before they could do anything, they argued.

***

The book won awards. In July 2022, I could barely speak from shock when it was awarded the Orwell Prize for Political Writing, making me – according to the Foundation that bestows it – the youngest ever winner of the prize. ‘The need now is not to speak truth to power but to tell the truth about power,’ said chair of judges David Edgerton about the shortlist. He called my book ‘an extraordinary exploration of a modern reality using modern means’. I got ‘the terrible truth out to a world that has been far too indifferent’.

In my subsequent speech, in London’s Conway Hall, I said that awards make me uncomfortable because they focus attention on the individual rather than the topic that they’re reporting on. I would be giving the £3,000 prize money to victims, I emphasised, and I followed through on that.

In September, My Fourth Time, We Drowned was awarded the Royal Irish Academy’s Michel Déon Prize, which is bestowed on what judges deem to be the best Irish non-fiction book of the past two years. But this one came with a bigger moral dilemma, as the prize money was €10,000, contributed by the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs. In that speech, at Dublin’s Mansion House, I said that I was unsure whether to engage with the award at all, given that the Irish government was implicated in the atrocities that my book documented, but I did it to help publicise the topic. Again, I emphasised that I would donate all prize money to victims.

An Irish political magazine called the Phoenix ran a report afterwards saying that attendees were forced to applaud my acceptance speech ‘with thunder on their faces’. ‘Incorrigible journalist Sally Hayden recently spoiled one of those feel-good occasions so beloved by Irish ministers when they posture as benevolent, first world statesmen comforting the afflicted,’ was its lede.

A month later, the book was shortlisted for the Baillie Gifford Prize, the UK’s most prestigious non-fiction prize. Next, it won non-fiction book of the year at the An Post Irish Book Awards; and in December it was named overall Irish Book of the Year. My phone filled up with ‘congratulations’ messages. In the days after these events, I woke up before dawn with my heart pounding, flashing back to the horrors the book contained. Was I just another privileged person reaping benefits from this ongoing tragedy?

I adopted a disconnect, forcing myself to forget the contents of the book so that I could go through the process of publicising it. ‘If a tree falls in a forest, does it make a sound?’ I would ask myself, reasoning that a book needed to find readers, and I was doing what was necessary to make that happen.

There were moments when my new-found composure was disturbed.

One came in September, when UNHCR Special Envoy for the Central Mediterranean Vincent Cochetel suggested on Twitter that grieving mothers should be ‘symbolically prosecuted’ when their children drown in the Mediterranean (subsequent calls for him to resign went nowhere).

Another arrived the following month, when EU foreign affairs chief Josep Borrell spoke at the opening of an academy for young European diplomats. ‘Europe is a garden,’ he told them, seemingly as encouragement. ‘Most of the rest of the world is a jungle, and the jungle could invade the garden... The gardeners have to go to the jungle... Otherwise, the rest of the world will invade us.’

The EU stepped up its anti-migration efforts. In June 2022, at least twenty-three people died while trying to enter Melilla, a Spanish enclave in Morocco. Journalistic investigations documented the brutal violence of Moroccan security forces. Yet, weeks afterwards, the EU announced it would ‘deepen’ its ‘cooperation’ with Morocco in efforts to stop migration. In October, the EU moved onto Egypt, signing the first part of an 80-million- euro deal aimed at staunching migration from there. Sudan erupted into war in April 2023, with paramilitary group the Rapid Support Forces, who are widely said to have - at least indirectly - benefited from and been emboldened by EU anti-migration funding, taking up arms against Sudan’s military. Shortly afterwards, the EU offered more than one billion euros of aid to Tunisia, despite president Kais Saied’s growing authoritarian and his mass arrests of the opposition. Tunisia had by then overtaken Libya as the North African that refugees and migrants were most likely to leave from.

All this time, deaths have continued. So far in 2023, at least 1,875 people have died or gone missing on the Mediterranean Sea, including around 600 who sailed from Libya and drowned off the coast of Greece on June 14. How have the mass drownings of people become in any way normalised? And when will there be a reckoning?

***

During events I spoke at, I was asked over and over whether there was any reason to be hopeful for change, and at the beginning I sounded quite a negative tone. But as the crowds got bigger, and more people told me they had taken the time to read the book, I would tell attendees that they were my reason for hope and they were the visible change I could see: the fact that people were reading, listening and learning meant something, though it is of course not enough.

I questioned whether people were listening to me because I was white, or because I was a Westerner. I also received messages from refugees and asylum seekers. ‘Harsh realities are amazingly brought to light. Thank you for the work,’ an Afghan man wrote. After one speech, a black Irish woman came up to me to say thank you, adding that if she had said the same thing no one would pay attention. That’s why it was important that this was coming from me, she said. That is, clearly, pretty messed up.

In the prologue to the book, I wrote that I hoped it would play some role in the quest for accountability. Now, I want it to make readers more actively question the world we live in: who is listened to; who is protected; who has access to justice; who gets sympathy? How many people have to be harmed so that the rest of us can live comfortably? Can we do better? We have to do better.

Sally Hayden, July 2023