Orwell's Roses

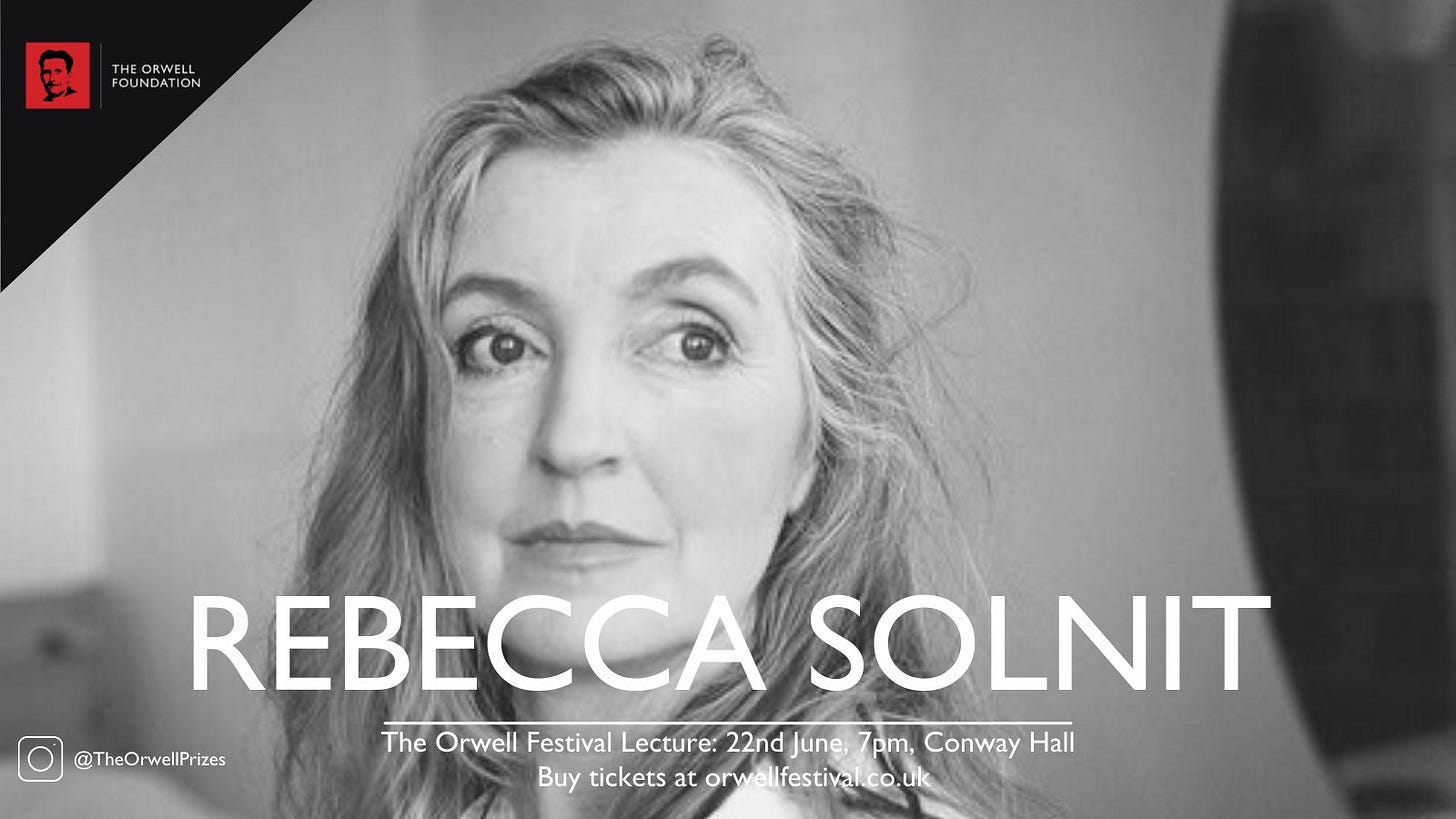

A review of 'Orwell's Roses' by Rebecca Solnit, who opens the Orwell Festival of Political Writing this Wednesday

The Orwell Festival opens this Wednesday 22nd June (7pm BST, central London and online) at an evening with the writer Rebecca Solnit.

In her Orwell Festival Lecture Rebecca Solnit will delve into themes from her book ‘Orwell's Roses’ (Granta) which was recently shortlisted for The Orwell Prize for Political Writing. She will explore Orwell’s involvement with plants, particularly flowers, and how they illuminated his other commitments as a writer and anti-fascist.

Book your tickets and see our full schedule of exciting events here.

Rebecca Solnit is the author of more than twenty books, including Orwell’s Roses. Her memoir, Recollections of My Non-Existence, was longlisted for the 2021 Orwell Prize for Political Writing and shortlisted for the 2021 James Tait Black Award. She is also the author of The Faraway Nearby, Wanderlust, A Field Guide to Getting Lost, A Paradise Built in Hell, Men Explain Things to Me and many essays on feminism, activism, social change, hope and the climate crisis. She writes is a frequent contributor to the Guardian. She lives in San Francisco.

Sarah Chambré’s review of ‘Orwell’s Roses’, below, was first published as a one of our monthly book reviews earlier this year. Our reviews provide an opportunity for students and early-career academics to discuss new non-fiction publications which contribute to our understanding of Orwell’s life and work. They give the views of the author and do not reflect the position of The Orwell Foundation.

Orwell’s Roses, Rebecca Solnit (Granta, 2021)

Roses need no help from humans. They crop up in nature and can propagate themselves largely unimpeded by our follies. As Rebecca Solnit points out, they have exploited us as much as we them; despite a reputation for high maintenance, they could thrive in a posthuman world. The rose has been co-opted by humans as a symbol of beauty, love, and English nationalism. We restrain their natural vigour: they have been tamed, genetically engineered, and commercialised. Solnit tracks down the roses planted by George Orwell in 1936 in a cottage garden in the village of Wallington, Hertfordshire, the writer’s home with his wife Eileen from 1936 to 1940. The planting of these roses is a recurring image to create an episodic biography of Orwell, connecting the pragmatic and personal gardener with the political writer, and to generate and intertwine essayistic reflections on a range of related topics. It puts centre stage Orwell’s delight in and appreciation of the natural world, anchoring his enduring political vision.

Solnit reminds readers that Orwell’s roses, almost certainly still blooming in his Hertfordshire garden, have borne witness to human catastrophes and the damage caused by capitalism and climate change. ‘[I]f war had an opposite, gardens might sometimes be it’ (Solnit, 2021: 5). She inverts and expands the concept of a saeculum – a person or living organism that witnesses, mutely or otherwise, vast spans of time – to structure her narrative: roses and the natural world as well as humans create her frame of reference. Using the patterns she finds in nature, she foregrounds the concept of community: we need to reorientate our world to (re)place humans as part of an ecosystem. Her book blends a description of Orwell’s maturation as a writer with her own wide-ranging reflections. These, both overarching and digressive, are inspired by his life and thought, his politics and aesthetics, linked by reference to his roses which offer a multitude of meanings from the practical to the symbolic. Orwell loved his Woolworths’ roses and his often expressed simple and inexpensive pleasure in them illustrates a desire to balance practical and aesthetic or joyful sustenance. Solnit’s phrase, ‘Bread and Roses’, which she traces back to the Women’s Suffrage movement of 1910, echoes through the book. Orwell stated that ‘I could not do the work of writing … if it were not also an aesthetic experience' (Solnit, 2021: 230). For Solnit, there is no conflict in this stance: ‘[p]olitics is the pragmatic expression of beliefs and commitments shaped by culture’ (Solnit, 2021: 95). Throughout the book, she guides readers to see how her approach is one that Orwell—a democratic socialist committed to rural husbandry—would care for and appreciate.

Solnit’s narrative style is entangled and layered, like the roses she describes. She circles around and returns to the date and the act of planting Orwell’s roses in 1936. This evokes a sense of actions and meaning playing out through a non-linear time, both reaching back to origins and stretching forward to bear witness to and imbricate the features of our present world. She justifies this cyclical framing as nature’s ‘patterns, recurrences, [its] rhythmic passages…’ (Solnit, 2021: 189). Orwell, like his roses, saw some of the most appalling tragedies of the twentieth century: two wars and the rise of two totalitarian regimes. He gives voice to these experiences in a way that remains relevant for us. Solnit’s depiction of the Spanish Civil War is typical of her style. She offers an analysis of the forces in this conflict, informed by the greater understanding that has emerged in the twenty-first century of Stalin’s crushing of the socialist revolution with the Allies’ collusion. Alongside this contemporary revisionist overview, she creates a detailed account of Orwell’s practical experience from his letters and Homage to Catalonia (1938). His almost accidental participation in the POUM Trotskyist forces gave him, as a participant, a clear view of the Stalinist threat.

For Solnit, this experience, and his research for The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) were transformative in Orwell’s maturation as a writer and gave urgency to his political message. Her contention that his interpretation and projection of the totalitarian menace of both Russia and Germany was well founded, in the face of decades of criticism from the left, is now accepted. It is her depiction of his daily engagement with and his celebration of the glimpses of the landscape that he was able to enjoy that makes her account more personable. She shows us here, as throughout this work, that Orwell’s writing is anchored in the commonplace. For him, and for Nineteen Eighty-Four’s Winston Smith, the land is emblematic of beauty and freedom. Like many interwar writers, his return from the Spanish trenches undermined this simple equation – it made him ‘ill at ease with the pastoral placidity he at other times cherished’ (Solnit, 2021: 115).

Solnit celebrates Orwell’s pragmatism – his roses and gardening are earthy and propagate in ways real and metaphorical. For her, ‘the antithesis of transcendent might be rooted and grounded’ (Solnit, 2021: 263). Using Orwell’s practical diaries, she evokes an authentic living within a community in the very literal grounding of Orwell’s life in vegetables and exchange. Her narration astutely enmeshes the material and cyclical eco-connections between the research and consideration which Orwell undertook for The Road to Wigan Pier. The creation of coal is a slow condensing of the prehistoric nature, recklessly released; coal has real connections to poverty and heat; the London smog from burning coal had a serious impact on Orwell’s health; our destructive carboniferous extravagance is a key component of the climate emergency. Orwell understood the disconnect between our consumption and our willing blindness to the conditions and consequences of production – his engagement with the conditions of the working class made him a socialist in ways that academic discourse had not.

Ecocriticism proposes that everything is interconnected and that there is no external neutral, disconnected, or privileged viewpoint. Orwell was able to understand and enunciate these complex connections. Man’s absurd and futile manipulation of his bounty to ultimately dead ends is a driving motivation in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). Solnit’s story of roses makes inevitable the deadening exploitation and commercialisation of the profit motive. Her evocation of despair in and her heartfelt sympathy with the workers in a rose factory in Mexico is wearily familiar – metonymic of warehouses and abattoirs across the world but nonetheless powerfully abject in its effect. The process of creating magic for the recipient of the roses is a paradigm of constructed and hollowed out desire – these roses are standardised, chilled, and denuded of scent. All the wonder or surprise that meant so much to Orwell has been literally cut away and edited out. In other episodes, she shows how scientific denial of agrarian fertility underpinned the Soviet mid-century famine. She situates the enclosure of English countryside as the corollary of the aristocratic passion for devised natural gardens and connects it with the flight of and exploitation of the English working class leading us, of course, to Wigan Pier. Her construction of the Orwell family tree connects to colonial crops of sugar and opium poppies, foregrounding the long-standing silence around the ever-present consequences and costs of enslavement, currently the topic of fraught debate. She suggests that Orwell’s downward mobility and political energy might enact a form of atonement.

Orwell’s pleasure in the quotidian romps through the pages. Rightly and pressingly, Orwell is an important writer for our times – his political analysis, criticism and satire have much to offer our concerns about democracy, indoctrination, and epistemological rupture. This book foregrounds Orwell’s fundamental beliefs in honesty, husbandry, and sharing. His intelligence, perspicuity, and prescience expressed in glorious prose makes him a writer for our and all times. It is notable that a preface for Animal Farm (1945) was written for the Ukrainian edition in 1947, where the survivors of the Soviet famines and purges readily appreciated his allegory. There is no doubt about his seriousness; Solnit reminds us in this hybrid biography of his joyfulness. Here was a man who, despite his deprivations, delighted in the everyday, in the simple, and in what we can find in beautiful abundance on this earth. Solnit shares her own celebration of this beauty, most vividly in her walk to Wallington. Here, she characteristically combines an appreciative evocation of the present pastoral beauty whilst connecting the rolling fields with the prehistoric past, the history of farming, and the sense of a saeculum that exceeds the human time frame. George Orwell, despite the tragic and well documented shortening of his life by respiratory illness associated with poverty and class, bounds enthusiastically off the final pages in his smallholding on the Isle of Jura, welcoming us to his self-created if unsustainable paradise on earth. In this awareness, joy, and generosity, he is an open-hearted, optimistic, and pragmatic ecologist.

Sarah Chambré is a PhD candidate at University College London (UCL), and an editor and reviewer for 'Moveable Type', the literary journal of the UCL English Department.