Masha Karp on the Ukrainian translation of Animal Farm

"They approved of almost all your interpretations."

This excerpt is from Masha Karp's upcoming book, Orwell and Russia, due to be published by Bloomsbury Academic. Masha Karp is a London-based freelance journalist with a special interest in relations between Russia and the West. She is a translator of Animal Farm into Russian (first published in 2001) and the author of the award winning first Russian biography of Orwell (St Petersburg: Vita Nova, 2017). She is a trustee of The Orwell Society and Editor of the Orwell Society Journal.

The story of Animal Farm in translation begins with its Polish edition. The book's first translator was Teresa Jeleńska, the wife of a Polish diplomat and a ‘”grande dame” in Italo-English literary circles’.[1] 5000 copies of her translation were published at the very end of 1946 by ‘Swiatpol’, the League of Poles Abroad based in London. Jeleńska corresponded with Orwell, elucidating some passages with his help, and was so fascinated by the fable that she tried to organise its translation into other languages as well. Her son, Konstanty Jeleński, who was 24 in 1946, had a friend of the same age – Polish-born Ukrainian Ihor Szewczenko.[2]

At the beginning of the 1990s, Szewczenko, who had become Professor in Byzantine Studies at Harvard (and changed the spelling of his name to Ševčenko), explained to Peter Davison: ‘Those post-war days... witnessed rapprochement between left-wing or liberal Polish intellectuals and their Ukrainian counterparts – for both sides realised that they had been gobbled up by the same animal.’[3] Jeleńska put Szewczenko in touch with Orwell and on 11 April 1946 he wrote to the author of Animal Farm: ‘I was immediately seized by the idea that a translation of the tale into Ukrainian would be of a great value to my countrymen’.[4]

Szewczenko was probably the first person to see how Animal Farm was affecting people from the Soviet Union who knew only too well the historical events behind the tale. Overwhelmed by the book, he immediately started sight-translating it ‘ex abrupto’ (without preparation) for groups of Ukrainian Displaced Persons (DPs) in the camps near Munich.[5] Among them was his wife, the daughter of Ukrainian poet Mikhailo Dry-Khmara, killed in Stalin’s concentration camp in Kolyma, and her mother, both sent into internal exile after the poet's arrest, and certainly many others with similar tragedies behind them.[6] In his letter to Orwell, Szewczenko attempted – in his rich, bookish and slightly awkward English – to give the author an idea of how his book was perceived.

‘Soviet refugees were my listeners. The effect was striking. They approved of almost all your interpretations. They were profoundly affected by such scenes as that of animals singing "Beasts of England" on the hill. Here I saw that apart from their attention being primarily drawn on detecting "concordances" between the reality they lived in and the tale, they visibly reacted to the absolute values of the book, to the tale types, to the underlying convictions of the author and so on. Besides, the mood of the book seems to correspond with their own actual state of mind.’[7]

“The mood of the book seems to correspond with their own actual state of mind.”

He also informed Orwell that ‘the attitude of the Western World in many recent issues roused serious doubts among our refugees’, who wondered ‘how it were possible that nobody “knew the truth”’.[8] ‘Your book’, he added, ‘has solved the problem.’[9] Orwell, naturally, granted permission to publish a Ukrainian translation and Szewczenko had it ready by autumn 1946. He then gave it to the Ukrainian publisher Prometheus in Munich and in early March 1947 wrote to Orwell again, this time asking him for a preface, as requested by the publisher. Although ‘frightfully busy’ Orwell did write this preface, which forever remained his most detailed explanation of the motives behind the “fairy story”.[10]

There is no doubt that one of the reasons he agreed to do it was Szewczenko’s sociological portrait of the publishers, ’who became genuinely interested in AF’. Szewczenko explained that they were for the greater part Soviet Ukrainians, many of them ex-members of the Bolshevik party, but afterwards inmates of the Siberian camps. They were the nucleus of a political group. They ‘stand on the "Soviet" platform and defend "the acquisitions of the October revolution", but they turn against the “counter revolutionary Bonapartism” [of] Stalin’s and the Russian nationalistic exploitation of the Ukrainian people; their conviction is that the revolution will contribute to the full national development. …Their situation and past causes them to sympathise with trotskyites, although there are several differences between them. Their theoretical weapon is Marxism, unfortunately in a somewhat vulgarised Soviet edition. But it could not be otherwise. They are men formed within the Soviet regime.'[11]

Szewczenko, who thought that these people were ‘representative of what any serious potential opposition inside Soviet Russia… could be like’, finished this passage by proudly adding: ‘AF is not being published by Ukrainian Joneses,’ which certainly was music to Orwell’s ears.[12] He wrote back: ‘I am encouraged to learn that this type of opposition exists in the USSR’.[13] The more precise and much less optimistic way of putting it would be to say that this type of opposition was then being destroyed in the USSR. After all, the people Szewczenko described were abroad and those within the country had a chance to survive only if they kept silent.

During the two years of its existence (1946-1948) Prometheus mostly published new Ukrainian literature – it was part of the Ukrainian Art Movement (MUR), an organisation of about 60 Ukrainian writers from the DP camps in Germany. Animal Farm then was a remarkable exception – a book by a contemporary foreign author with his own preface!

Szewczenko later admitted to ‘an unpardonable sin against literature’[14] – taking advantage of Orwell’s permission ‘to cut out as much as you wish’, he edited out several sentences which he thought unsuitable for Western Ukrainians, who were Polish citizens till 1939 and constituted, by his estimate, about a half of the prospective readership.[15] It is impossible to establish exactly what ‘unsuitability’ he meant, because, unfortunately, Orwell’s original preface had been lost and what survives today is a back translation from the Ukrainian – obviously without the material cut by Szewczenko.

In his preface Orwell tried to build a bridge to Soviet citizens he knew little about, explaining both things too remote for them to understand – what English public schools were like and what kind of country Britain was – and his own ‘attitude to the Soviet regime’.[16] He stressed not only his reluctance ‘to interfere in Soviet domestic affairs’, but even his refusal ‘to condemn Stalin and his associates for their barbaric and undemocratic methods’.[17] Yet with the same vehemence he stated:

'It was of the utmost importance to me that people in western Europe should see the Soviet régime for what it really was. Since 1930 I had seen little evidence that the USSR was progressing towards anything that one could truly call Socialism. On the contrary, I was struck by clear signs of its transformation into a hierarchical society, in which the rulers have no more reason to give up their power than any other ruling class.'

Orwell’s original preface [has] been lost: what survives is a translation from the Ukrainian.

Having explained ‘why ‘totalitarianism is completely incomprehensible… to the workers and intelligentsia in a country like England’, Orwell named as the aim of his book ‘the destruction of the Soviet myth …essential’, he insisted, ‘for a revival of the Socialist movement’.[18]

The first edition of Animal Farm in Ukrainian, published in September 1947 with Orwell’s preface, did not have a happy fate.[19] Orwell wrote to Arthur Koestler: “the American authorities in Munich have seized 1500 copies of it and handed them over to the Soviet repatriation people, but it appears 2000 copies got distributed among the DPs first.’[20] Whether this was the failure of an attempt planned by Ukrainians ‘to smuggle some copies among the Soviet soldiers’ in Germany, which, as Szewczenko suspected from the start, involved risks for both sides, or just an incredible naiveté on the part of the American authorities, is not known.

And yet 2000 books reached their readers and many were carefully preserved by Ukrainian families in Germany.[21] Despite the failure of the first endeavour, Orwell was not ready to abandon the idea of sending Animal Farm to the Soviet Union.

Unless stated otherwise, the notes to this article refer to The Complete Works of George Orwell, XX vols, edited by Peter Davison, London: Secker & Warburg, 1998.

[1] Editorial notes to Szewczenko’s letter to Orwell, 11 April 1946. XVIII, 237.

[2] In 1952, Konstanty Jeleński, aged 30, became Head of Central European programme of the Congress for Cultural Freedom.

[3] Quoted in: 'Editorial notes to Szewczenko’s letter to Orwell, 11 April 1946. XVIII, 237.’

[4] Szewczenko to Orwell, 11 April 1946, XVIII, 235..

[5] Ibid., 236.

[6] See: Andrea Chalupa, Orwell and the Refugees: the Untold Story of Animal Farm (2012), 10.

[7] Szewczenko to Orwell, 11 April 1946, XVIII, 236.

[8] Ibid., 235-236.

[9] Ibid., 236

[10] Orwell to Szewczenko, 13 March 1947, XIX,73.

[11] Szewczenko to Orwell, 7 March 1947, XIX, 72-73

[12] Ibid.

[13] Orwell to Szewczenko, 13 March 1947, XIX, 73.

[14] Quoted in: ‘Editorial notes to Orwell’s letter to Szewczenko, 21 March 1947, XIX, 85.'

[15] Orwell to Szewczenko, 21 March 1947, XIX, 85.

[16] Preface to the Ukrainian Edition of Animal Farm [March 1947], XIX, 87.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid., 88.

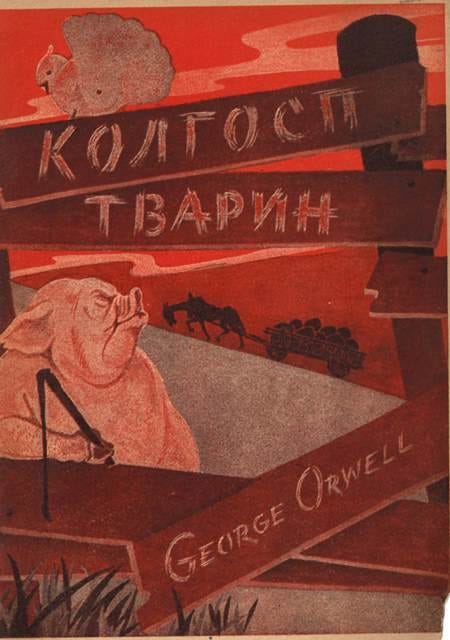

[19] Szewczenko, who published his translation under the pseudonym Ivan Cherniatynckyi, strengthened the similarity of Orwell’s tale with Soviet realities by translating its title as Kolgosp Tvarin (The Kolkhoz [Collective Farm] of Animals).

[20] Orwell to Koestler, 20 September 1947, XIX, 206-207.

[21] See: Chalupa, Orwell and the Refugees, 8.