Why it's time to start taking young people seriously

Young people need an education fit for the world they live in

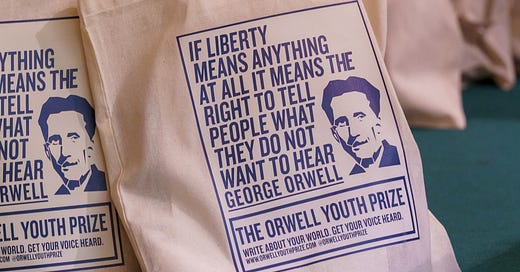

In this special report, The Orwell Foundation’s Deputy Director Liz Wallace and Rethinking Poverty’s Barry Knight reflect on what our shared work reveals about young people’s political engagement and education in the UK.

The Future We (Didn’t) Want

In 2019, in partnership with Rethinking Poverty, the Orwell Foundation embarked on an ambitious project to bring together young people from across the United Kingdom to think creatively about how to build a better society. We wanted to learn what young people wanted from the future, but also how they were thinking about it.

Rethinking Poverty supported the project because its earlier work showed that, given the opportunity, children and young people can see solutions to problems that adults can’t. Young people are often held up as the hope for the future, but do they have the tools to bring about the changes they want to see? And is anybody listening?

In 2020, following lockdown and the Orwell Youth Prize’s rapid transition to an online programme, we received more entries than ever before. As the pandemic enforced round-the-clock home-living, young people flocked to the programme. The contact that individual feedback provided became even more valuable as a source of both advice and affirmation. There was also, perhaps, more time available to some young people, as the narrowness of the contemporary curriculum eased away.

“Rather than the future they wanted, young people were sending us dystopian visions of the future they desperately wanted to avoid.”

The theme we had asked young people to respond to was ‘The Future We Want’ and the rise in entries and the passion with which young people wrote is indicative of a generation more engaged than ever. Yet, right from the outset, our team of volunteer readers also noticed a striking pattern: rather than the future they wanted, young people were sending us dystopian visions of the future they desperately wanted to avoid.

At first glance this might seem unsurprising. These young people were entering an award bearing the name of one of the world’s most celebrated writers of dystopian fiction! Add to that the unprecedented challenges and fears of a global pandemic and no wonder young people were struggling to see above the chaos.

But when we looked beyond the subjects and considered how young people were writing, the issue went deeper still. Through a detailed, thematic analysis of the words young people were using when it came to writing about climate change in particular, we identified a lack of political literacy, especially at a local level.

Young people were writing articulately about the worries they harboured about what was happening in the world around them, but they lacked the tools with which to channel that concern into action which might help improve the situation: at its most simple, this could be seen in the way many entries would ‘answer’ the question with a list of ‘wants’, without any indication of the steps to get there.

The Orwell Youth Prize and Political Literacy

The Orwell Youth Prize seeks to address exactly this lack of political literacy by encouraging young people to think and write about the way power operates at a local and national level, and to explore how their own experiences connect to wider debates in society. We also bring young people into direct contact with those with the ability to implement their ideas. Our entrants also want their own work to be read by writers: our unique feedback system, with every entry read and commented on by an expert volunteer, who also provides suggestions about how to further explore their ideas and use language more precisely, is in some ways the most powerful thing we do.

“If most young people aren’t thinking about politics, it must at least be in part because politics isn’t thinking about them.”

Understanding how to make change happen is one thing, but young people also need to believe it is possible: if most young people aren’t thinking about politics, it must at least be in part because politics isn’t thinking about them.

The Orwell Youth Prize is committed to taking young people seriously. As well as giving our entrants a collective voice through our research, we promote our winners as writers and thinkers in their own right, alongside the winners of the prestigious Orwell Prizes, which are open to adults. So, for instance, we secure responses to our winning entries from experts on various topics, such as climate change, sport and politics, as well as leading writers, campaigners and politicians.

In recent years, we have secured the Youth Prize a platform on BBC Radio 4’s flagship news programme and have begun sharing winning work directly with each winner’s member of parliament. Central to this work is ensuring that our young writers are engaged with as equal citizens. When we ran podcasts with Compass featuring our Youth Fellows and a range of politicians, writers, journalists and policy makers, they were not so much interviews as conversations, with guest speakers questioning Orwell Youth Prize winners about their own work and ideas. Our research was also presented in an online event as part of the 2022 All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Political Literacy, in collaboration with Shout Out UK.

“Dawn Butler MP saw that it was Manal’s own words that were the best way to start a national conversation.”

So far, the results have been positive in some respects, but less so in others. Many politicians have sent personal messages of praise to prize winners commending them for their passion and clarity of thought. Chris Law MP (SNP, Dundee West) was left “feeling empowered to do more in my role in Parliament”. Dawn Butler MP (Labour, Brent Central) was so impressed by meeting one of our Youth Fellows, Manal Nadeem, that she quoted from Manal’s work in a speech in the House of Commons. Dawn Butler saw that it was Manal’s own words that were the best way to start a national conversation.

But there is more we can do to encourage continued engagement: after meeting the APPG, one of our Fellows noted that, although parliamentarians seemed interested in their ideas, there was no follow up, ‘so it was hard to tell if the presentation had a lasting impact on the group, or if they’ve incorporated our ideas into any future plans’.

Ultimately, if young people are going to take an interest in politics at a local and a national level, we also need to see politicians and leaders following our lead by going out of their way to hear from young people directly. Programmes like the Orwell Youth Prize and organisations like Rethinking Poverty have an important role to play. But it’s time we all started taking young people seriously.

An educational failure

Failure to pay heed to this warning will have harmful long-term effects on our society. If you think ahead 20 years when today’s children and young people begin to take up senior leadership positions in our society, we may have a cohort of people in charge who are both anxious and pessimistic about the future but have little agency to change things.

The roots of the problem lie in the education system. Ken Robinson has demonstrated time and time again how the school experience diminishes creativity by its requirements for conformity, compliance and standardisation. We put children through Standard Assessment Tests (SATs) that cause anxiety in children while research demonstrates that anxiety interferes with learning.

“It is time to revise the GCSE curriculum to ensure that education is fit for the world that children will live in.”

The extent of this anxiety was evident in the Orwell Foundation’s study of entries about climate change. It also showed that the education system does little to abate it. While children are taught about the problem of climate change in geography and science, they are not taught what might be done collectively to improve it nor about tools that are available. Many young people are terrified about the problem and have little idea what can be done about it. Surely, it is time to revise the GCSE curriculum to ensure that education is fit for the world these children will live in.

Liz Wallace and Barry Knight

Liz Wallace is the Deputy Director of The Orwell Foundation. Liz joined The Orwell Foundation from the BBC’s Westminster newsroom, where she had been a Political Reporter and Editor.

Barry Knight is the author of Rethinking Poverty: What makes a good society? He was the director of the Webb Memorial Trust and has written books on economic development, family policy, inner cities, the voluntary sector, and social enterprise.